Despite numerous credits in magazines of the time, the author of this story seems to have completely fallen off the radar. As far as we can tell, his writings haven’t been transcribed, collected, or widely shared online, although some may survive (like this one did) in PDF scans of old periodicals.

In fact, at the time of writing, “The Last Skipper of the Lapwing” has only five hits on Google, which is a shame, because it’s a fairly effective nautical ghost story. Hopefully we can do our bit to rescue it from obscurity!

We’ll be posting many short stories like this one, so make sure you follow us and check in regularly.

“Master wanted for a 1,000-ton steamer. Immediate employment offered. Knowledge of China Seas indispensable. No investment necessary. Apply at once, with testimonials, to Messrs. Mavis, Gray and Co., Hong Kong.”

The above advertisement used to appear with more or less regularity in the columns of the China Mail every three or four months. At first a single insertion appeared sufficient, but as time went on it might sometimes be noticed running for several consecutive numbers. After a while most of the regular Hong Kong skippers grew to know to what ship it referred. Still, it must have been constantly answered by outsiders from other ships, or other trades. These, however, can never have retained their command for long, for the advertisement invariably re-appeared after an interval to announce that the “Lapwing” was again without a master. There was no doubt she was a most unpopular ship. Yet it was difficult to ascertain the cause. Most people, if asked, said they could not understand it. A few looked as if they could tell something if they chose. No one seemed to have any definite knowledge—or if they had they kept it to themselves.

Now I have learnt the reason. Now I understand why the command of that vessel passed from man to man till the phrase, “skipper of the ‘Lapwing,’” raised a smile on Hong Kong lips. Now I know not only that it is a fact that every captain, save two, left that ship after the first round voyage in her—and of the two exceptions one was washed overboard in a typhoon, and the other committed suicide—but, also, I know the reason why!

Some months ago, Jack Forrester and I ran up against each other most unexpectedly in old Ambrose’s store at Hong Kong—a noted gathering-place for officers of the merchant vessels trading to and from the port. We had been friends ever since we were boys, and, consequently, we hailed each other with genuine delight after the years that had elapsed since our last meeting. I was, by this time, first officer of one of the Indian mail boats then running between Hong Kong and Calcutta, and he had recently been master of a China coaster that plied mainly between Shanghai and the southern ports.

When the war broke out between China and Japan his owners promptly sold their vessel at a good price to the Japanese, and he lost his berth. Times were bad, and he had not yet succeeded in getting another ship—so he told me as we sat over our drinks at the rough store table. Then we talked of many things: of the happy days spent as cadets together in the dear old training ship on the Mersey; of apprentice days round the Horn in a ‘Frisco wheat ship; of vessels that we had sailed in, and vessels that we had seen from afar: of board of trade examinations, and the long, weary struggle up the ladder of a sailor’s profession. From that the conversation turned back again to homes in England, and I asked him if he was married.

“No,” he answered, with a sudden flush on his bronzed face, “but I am engaged.”

“My best congratulations, old fellow”—I was beginning conventially, when he cut me short with abruptness.

“Her name is Jessie Collier, and she is governess in the family of an English merchant named Price at Shanghai,” he said, in rather troubled tones. “And, of course, I think her the sweetest girl on earth, Frank. But in another three months the family are returning to England. Unless I can get a berth before then, and one, moreover, which will enable me to marry her and take her with me, she will have to go back with the Prices. The thought of it is worrying me badly.”

Just at that moment, before I could reply, someone, quite by chance, flung down on the table beside us the current copy of the China Mail. Jack picked it up carelessly, and there was the advertisement about the “Lapwing” staring him straight in the face. He pounced on it eagerly with a quick exclamation. In five minutes he had departed unceremoniously, leaving me to cut the fatal slip out of the paper and speculate idly on its real meaning. I have that very cutting in my possession still.

Two hours later I met him again in the street. He was radiant with delight. He had gone direct from Ambrose’s store to the office of Messrs. Mavis, Gray & Co., to apply for the post, and had obtained it on the spot.

It was in vain that I hinted, at first slightly, and then, after a while, more plainly, that he ought not to have been so precipitate. That the ship might not perhaps be a desirable one. That if it was the first-class berth that he declared it to be, it was at least peculiar there should have been such an evident absence of competition for it. Growing more explicit, I warned him that there were curious rumours afloat; that more than one skipper had left the “Lapwing” in the greatest hurry. That none had ever remained, so it was said, more than three months in her, and that although, strangely enough, the same did not apply to the crew, yet the high wages offered by Messrs. Mavis, Gray & Co., to the masters of their desirable 1,000-ton steamer, invariably proved of no use in retaining their services for any lengthy period. It was even whispered that the bad end of her first skipper—he who had committed suicide—had something to do with the aversion felt by his successors for their vessel.

But Jack Forrester scoffed at the idea, and ridiculed my indefinite warnings. He laughingly declared that it would take more than all the ghosts of all the skippers that had ever had her, to prevent his accepting the command of the “Lapwing” on the terms offered by the owners. Never, he averred, had such a stroke of luck turned up so opportunely. Mr. Mavis, the senior partner of the firm, had been so pleased with Jack’s testimonials that the latter had ventured to ask him whether, after the first voyage, he might be allowed to take a wife with him. And the tall, courteous old owner, looking gravely at his new captain from under his bushy, grey eye brows, had replied, after a momentary hesitation, that he thought there would be no objection—provided, of course, he remained in command when the time for the second voyage came. Which highly significant proviso—as I thought it—Jack treated as merely the ordinary caution of a shipowner’s business.

And, forthwith, we went off to have a look at the steamer. She was lying abreast of the lower part of the town on the far side of the fairway channel, engaged in taking on board bunker coal from a large lighter alongside. Consequently, everything was plentifully besprinkled with coal dust. Her two pole masts were grimy in the extreme, and recent brine-whitened patches on her funnel were rapidly assuming a more sooty colour. Her iron decks, in places, were distinctly rusty. But she was not at all a bad ship of her kind. Built on the Tyne about five years earlier, she was a steel boat with triple expansion engines, and many modern improvements. One peculiarity of her construction was that all the berths for the officers and engineers, as well as their mess room and the steward’s pantry, were amidships; the skipper’s cabin and a tiny saloon being situated aft by themselves. This arrangement seemed to me rather unusual, and I drew Jack’s attention to it.

“Oh—that does not matter,” he answered promptly, “I always sleep in the chart room under the bridge at sea, so as to be available at once in case of necessity.”

“You won’t be able to do that aboard this ‘ere ship, sir,” commented the mate, who was showing his new skipper round. “There ain’t no proper chart room so to speak. All the chart room we ‘as is a bit of a table and some drawers at the back o’ the wheel’ouse.” And this fact was speedily confirmed on investigation.

“The cap’n allus ‘as to sleep aft,” continued the mate, who struck me as wishing to emphasise the fact. “Bit lonesome at times I’m thinkin.” And the speaker blinked queerly in the sunlight.

Isaac Smerton, as the mate called himself, was a rough battered looking individual, one of those men who never rise above subordinate rank, but, sturdy and hardworking, are content with the lesser responsibilities of life. A splendid seaman in his uncouth way who had voyaged in almost every corner of the globe—from Mauritius to Honolulu, from Alaska to the Cape—he had, so he told us, come out with the “Lapwing” from England on her maiden trip, and remained in her ever since.

“Aye, she ain’t such a bad boat,” he opined slowly, “though not the sort o’ craft as you’d make a yacht of. A bit too much given to rollin’ when she ain’t full that’s what she is; and contrary-like she pulls strong on ‘er ‘elm when deep. But she don’t seem to suit her skippers, them as lives down aft. Lord! What a ‘eap I’ve ‘ad over me. ‘Bout full moon ’tis mostly as they gets uneasy too.”

“Full moon!” exclaimed Jack in surprise. “Why what has that got to do with it?”

“Can’t say, sir, I’m sure,” answered the other shrugging his shoulders and looking his questioner straight between the eyes. “Never did rightly understand it myself. But ’tis a fact for all that. Maybe you’ll find out before long sir,” he added rather significantly.

“I wonder they have not given you the command,” I remarked with some curiosity.

“Wouldn’t ‘ave it, sir,” he replied promptly. “I knows a good berth when I gets it. I’m mate of this ‘ere craft and I sleeps ‘midships and I’m content like. Mr. Mavis ‘e offers me the ship two year ago come next week. ‘No thank ye, sir,’ I says, ‘mate I am and mate I’ll stay.’ But now I’ll just be lookin’ after them thieves forrard by your leave, sir.”

And, straightway, Mr. Smerton departed in some haste, while from the hubbub that shortly afterwards arose in the bows we judged his presence was not unneeded.

“What does the old fool mean, Jack?” I asked my companion as we went down into the little cabin aft to drink to a prosperous voyage from certain stores abandoned by the last skipper, who had departed—so unkind rumour alleged— without even the formality of getting a discharge.

“I don’t know and I don’t care,” answered the “Lapwing’s” new master curtly. Then his honest, sunburnt face flushed slightly as he added:

“I have got to make a home for Jessie in three months’ time, you know. So I cannot afford to be too particular. Here is luck to us all three!” he said.

As I put down my glass, after drinking heartily to his toast, I swear that I distinctly heard a low mocking chuckle at my side. I glanced sharply round the dusty little saloon in astonishment. Of course there was nothing there. I got up and walked to the door. Jack, apparently quite unconscious of it, was overhauling an empty locker. So far as I could see no one was near the companion ladder or by the cabin skylight overhead. Could it have been merely imagination? I suppose it was—and yet?

But my chum speedily cut short my wondering by declaring that he must return ashore to fetch his kit. The ship was to sail almost immediately. And so my visit to his vessel was at an end. And as I went overboard I felt a distinct reluctance to refer to that curious sound. So I didn’t.

Both the “Lapwing” and my own ship cleared from Hong Kong the same evening. We left just after her, and steaming rapidly seawards, passed her outside the entrance to the harbour. It was my watch, and as I paced the bridge I could see Jack’s tall form standing by the binnacle on the other craft. We waved mutual farewells. For my part I thought he was a fool to go. There seemed to me an air of mystery about his ship that puzzled me and which I did not like. But then I had no Jessie Collier to consider. Perhaps, if that had been the case, my point of view would have been different. I have never married yet.

I was back again in Hong Kong before many weeks had elapsed, and I enquired at once for the “Lapwing.” But she was still away on some round voyage to the Philippines and Java, and there was no news of her. Then I was sent on an intermediate run to Rangoon, and it must have been a good two months later before I found myself opposite Jack Forrester again in a cosy corner of Ambrose’s hospitable store. I was just in from Calcutta; he was off next morning for Labuan and the Straits Settlements.

He seemed unusually grave, and at first was very uncommunicative. But after a time he threw himself back in his seat, lit a fresh pipe, and told me the whole yarn that follows quietly and thoughtfully. I think it was a relief to him to have some one to talk to about it whom he could trust. As far as I can remember this is how it ran, more or less in his own words

“There is something uncanny, something horrible about that boat of mine, Frank, that baffles me. I never knew what fear was till I joined her, but I think I understand the feeling well enough now. Just about the full moon—as old Smerton hinted in our first interview, do you remember?—the evil things seem to have power to manifest themselves. Evil they certainly must be too! I used to laugh at stories of ghosts and spirits; I do it no longer, I can tell you.

“For some time after leaving Hong Kong all went well. Once or twice I thought I heard curious sounds in the cabin for which I could not account; but as I was accustomed to have it all to myself, except when the steward was about at meal times, I put them down to fancy. The night before the moon was full we were steaming through Mindoro Strait on the way to Manilla. The heat all day had been fearful, and the tropical evening had brought no respite, it was close and sultry. The sea was smooth save for a slight oily swell from the northward. A few ghostly gleams of phosphorus broke from the ‘Lapwing’s’ bows as she made her way sluggishly against the set of the current. I had been on the bridge till we were safely past Apo reef, which divides the strait in two, and then shortly before eight-bells, midnight, I went aft to get some sleep. A strange feeling of depression had been creeping over me all day and by this time it had become almost insupportable. My cabin, as I dare say you recollect, has two doors, one in the passage and the other into the little saloon. On this occasion I made straight for my bunk without passing through the latter, and I was in the act of turning up the little swinging lamp when a sudden most unexpected noise made me pause in astonishment.

“Next moment it was repeated. A distinct burst of hoarse laughter rang out boisterously from the saloon itself.

“I confess I was startled. Who on earth could be there at this hour of the night? But then it occurred to me that the steward must be making free with my whisky, and I flung open the door angrily, intent on giving that gentleman a lesson.

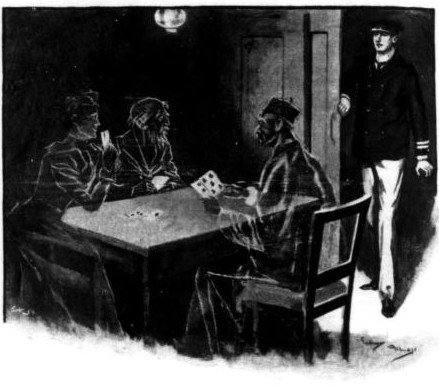

“The words died on my lips. At the table were seated three strange forms. The lamp was burning brightly, and shed a vivid light on them; every detail is burnt on my memory. One looked like a Chinaman. Opposite was what appeared to be a burly, red-headed man, in a dirty sailor-blue suit, minus a collar, smoking a black clay pipe upside down, the ashes from which strewed a long thick beard. This latter appearance was wild and uncouth in the extreme; I can hardly describe the impression made on me in words. I can only think of it with a shudder.

“The third shape was a woman’s. It was sitting in my armchair at the head of the table, leaning carelessly backwards. It was the dress that struck me as so extraordinary, for every colour there is seemed to be blended in one hideous glare that made my eyes ache to look at it. It, or rather she, was busy sorting a pack of greasy cards, and her face was hidden behind them. Her hands were white and active.

“I never was so completely taken aback in my life. Everything looked solid and substantial, from the sailor’s ragged cap on the floor to the black spirit bottles on the table. And yet the faces made me shiver. On all of them—for the woman was gazing straight at me now with piercing black eyes—was stamped the same fierce expression, the same reckless, abandoned look. One felt there was nothing, however wicked, such people would not dare; no deed however cruel they might not attempt if it suited them.

“My entrance was greeted with a rude shout.

“‘Here is a partner for you, Nell,’ cried the man in a rasping voice. ‘You two can take on Ah Fung and me. Whist, mate, that’s the game!’ And he motioned me imperiously to a seat opposite the woman.

“I suppose I must have taken it mechanically, for I found myself shuffling the cards like a man in a dream. They certainly seemed real enough. I can almost feel the touch of them still.

“The shape opposite me gave a horrible little laugh.

“‘The usual stakes?’ demanded its woman’s voice, shrilly.

“‘Aye, that’s it,’ agreed the other; while the Chinaman rocked backwards and forwards and peered at me. ‘Look ye here, mister; you think you’re master of this ship, I reckon. So did others afore ye. But that is where you are all mistaken. There is only one skipper aboard this craft, and that is me! And I am going to have my way. This ship’—the thing that was speaking thumped the table furiously till the bottles rang—’has got to be lost—to go to the bottom. Do you understand? Maybe you have a kind of objection to sinking her. So did some of the others in your shoes; and those are the lucky ones that shifted quietly, I can tell ye. But I’ll make a sportsmanlike offer. We’ll play for it. The ship’s safety shall be the stake; that is a fair game, ain’t it? If we wins the rubber, you sinks the ship. If you and Nell there’—with a ghastly leer—’beats us, then the old tub floats. See? Play up, Ah Fung, you son of a pig—your lead!’

“And he kicked his partner under the table till the latter screeched with anger.

“We played that awful game, those three shapes and I. I have the reputation of being rather good at whist. But I do not remember in the slightest how it went that night. All I know is that a sudden fiendish yell of triumph warned me that I had lost. And I became aware of those horrible mocking faces glaring fixedly into mine.

“An indescribable feeling of terror seized me. I sprang to my feet, scattered the cards in all directions, and rushed madly on deck. Their last threatening chorus rang in my ears:

“‘Lose the ship before we meet you at next full moon, or face us again if you dare.’

“And its discordant echoes haunted me along the quiet decks, up the bridge ladder, and even while I stood beside the mate, looking mechanically into the glowing binnacle at the restless compass card.

“But I am not going to be scared away from the ‘Lapwing.’ Neither, of course, am I going to lose her if I can help it. Last full moon we were lying in Batavia harbour, and I confess I spent the nights ashore. But during the next one, in about ten days’ time, we shall be at sea. Then I will face it out, and tell you the result when we meet again.”

I begged him, with the utmost earnestness, not to be so rash. I urged, I argued, I entreated, and at last I cursed his obstinacy. Then only I learnt the reason of his determination.

“Jessie sails with me this voyage, Frank,” he said slowly. “She knows all the story, and has made me promise to go and take her with me. We were married two days ago.”

I stared at him in silent surprise, and after that I gave up my attempt to dissuade him. Moreover, when, later on, he introduced me to his young wife, I ceased to wonder. There was that in the girl’s clear dark eyes, and sweet, rather wistful face, that made me in some degree realise how a man would risk everything for the sake of keeping her with him.

Besides, in this matter she herself was resolute. If such a girl had ever wished me to do anything for her, I should have done it unquestioning. Alas! None such ever has. And Jessie Forrester had heard her husband’s story, and had declared that her place was to face the evil things at his side, come what might. And she had made Jack, who loved her, reluctantly acquiesce. Of what use, then, was argument of mine?

They sailed next morning at sunrise, and I watched them go with a dim foreboding, for which I could not account.

One evening, rather more than a week later, my own vessel was steaming rapidly southward towards Singapore. The night was fine, with a light breeze, the sea smooth, and the moon, approaching her full, was bathing every thing in a wondrous glory of silver hue. Dinner was over, and the passengers aft were having a dance. It was my watch on deck, and as I paced the upper bridge the waltz music hummed dreamily in my ears. All that day a vague sense of approaching calamity had haunted me, mixed up in some strange fashion with thoughts of the “Lapwing” and her crew. Once that evening I could have sworn I heard Jack’s voice calling me. Another time it was as if Jessie’s low tones came across the rippling waters in a cry for help. Of course, it was all imagination. The heat in the daytime had been stifling, and I had not been able to get my due share of sleep.

But what was that glare away to the southward? Suddenly, interrupting the music and the laughter on the after deck, a hoarse shout broke from the man on the lookout forward:

“Strange light on the port bow, sir,” his voice rang out ominously. Then a minute or two later, “ship on fire ahead, sir!”

The dancing stopped abruptly. There was a general rush to the side rail. The captain joined me on the bridge, and ordered me to alter the course to bring us close up to the burning vessel. He rang up the engine room to “stand by.”

The distance between us lessened rapidly. Soon we were able to distinguish the outline of a steamer lying motionless in the midst of a circle of flame-coloured sea. The fire was bursting out furiously, and mounting upwards till the very sky above was reddened with the glare. As we steamed nearer, fresh volumes of flame and smoke could be seen breaking out along her decks, whilst we seemed almost to hear the fierce crackling of the woodwork and the dull hissing of the flames.

But she appeared to be deserted. There were no signs of life on board.

“Can you make out her name?” said the chief to me, as the sharp “Ting Ting” of the telegraph carried his orders to the engine room to slow down.

I steadied my glass on the canvas wind screen of the bridge, and directed it on the bows of the doomed steamer. Long and earnestly I looked. Then a mist seemed to steal over my eyes as I spelt out the white letters one by one—”L-A-P-W-I-N-G.”

“I shall not go any nearer,” said the chief decisively. “Take one of the boats and make sure there is no one on board,” he ordered. And the throb of our propeller slowed away and then stopped.

The boat’s crew gave way with a will, and we were soon as close to the burning vessel as I dared approach. As it was, the heat of the fire was almost unbearable. We hailed her again and again—no answer. Once indeed my shout seemed to linger curiously, as if it were caught up on board and repeated in derision. But I must have been mistaken. She was low in the water, and from where I stood I could see no living thing on her scorching decks. Her boats had been cleared from the davits and were gone.

I gave the order to return. As the men pulled round we went quite close under the “Lapwing’s” stern. Tongues of flame were shooting out all round it and licking hungrily at the unburnt sides. And there, looking out of one of the cabin port holes, I saw a face. A face such as no honest man should see! A face the likeness of which—please Heaven—I shall never gaze on again! Its weird fiery eyes glared at me with the sinister triumph of evil accomplished at last. A terrible grin played round its white mocking lips. A second only was it there, and then there remained but the darkness of an empty port hole, through which the smoke was creeping.

A deadly fear seized me. I shouted incoherently to the men to row for their lives, and fell back into the sternsheets like a man that is stunned.

From that day to this I have never seen anyone connected with the ill-fated “Lapwing.” when I reached Calcutta at the conclusion of the voyage, I was transferred on promotion to one of the European going liners. After a while I learnt that the crew of the lost vessel were reported to have taken to their own boats, and to have been picked up by a passing Dutchman previous to our arrival on the scene. From the same source I gathered that the origin of the fire, which was supposed to have commenced in the captain’s cabin, was wrapped in mystery. So far as I know it has never been explained. And though I have made every endeavour to trace my friends the Forresters, as yet my efforts have been in vain.

Now I am to go back to the East again to command a fine new steamer in the China Seas. Perhaps before long I shall grasp Jack’s sturdy hand as of old and look into his wife’s sweet face once more. Perhaps at last I shall hear the conclusion of the strange weird tale.

Who knows?