The following story was published by Ainsworth’s Magazine in 1846. Unfortunately, we don’t have any biographical information about the author, other than his name.

We’ll be posting many short stories like this one, so make sure you follow us and check in regularly!

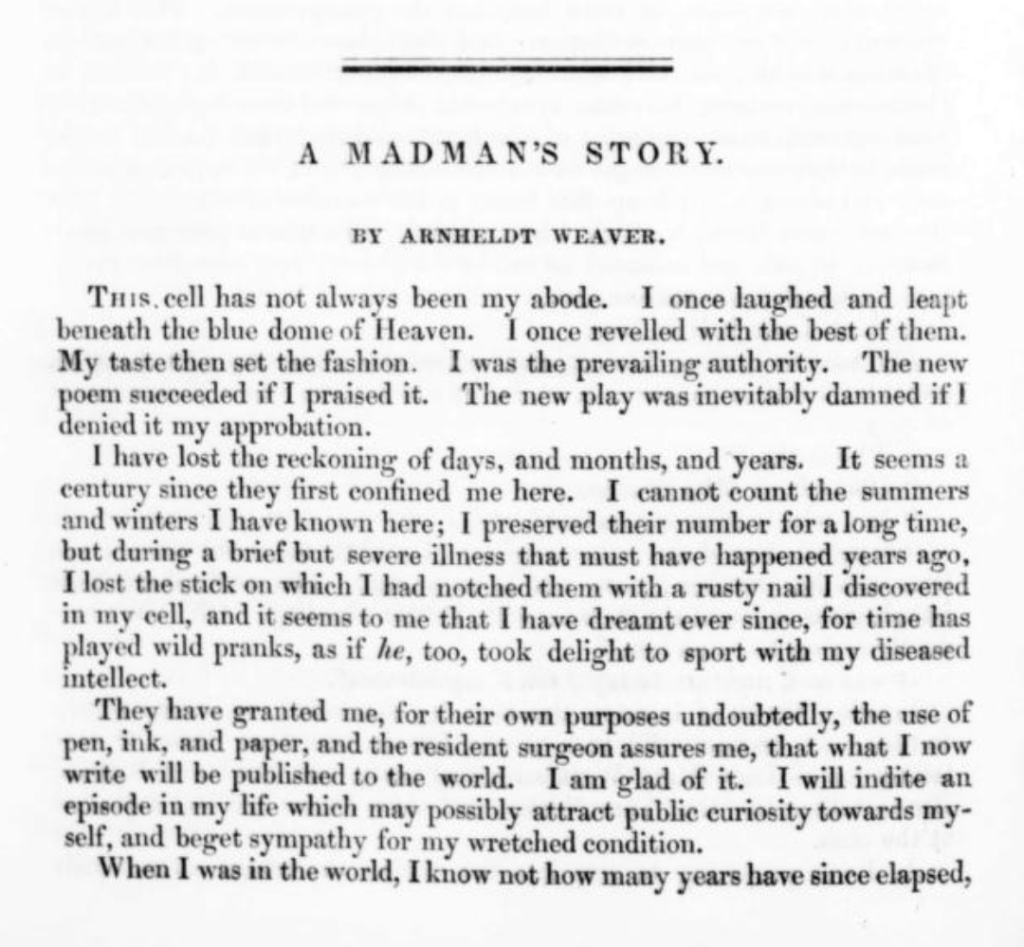

This cell has not always been my abode. I once laughed and leapt beneath the blue dome of Heaven. I once revelled with the best of them. My taste then set the fashion. I was the prevailing authority. The new poem succeeded if I praised it. The new play was inevitably damned if I denied it my approbation.

I have lost the reckoning of days, and months, and years. It seems a century since they first confined me here. I cannot count the summers and winters I have known here; I preserved their number for a long time, but during a brief but severe illness that must have happened years ago, I lost the stick on which I had notched them with a rusty nail I discovered in my cell, and it seems to me that I have dreamt ever since, for time has played wild pranks, as if he, too, took delight to sport with my diseased intellect.

They have granted me, for their own purposes undoubtedly, the use of pen, ink, and paper, and the resident surgeon assures me, that what I now write will be published to the world. I am glad of it. I will indite an episode in my life which may possibly attract public curiosity towards myself, and beget sympathy for my wretched condition.

When I was in the world, I know not how many years have since elapsed, but George the Fourth was on the throne, and he must have died ages ago, I displayed a dual character. One while I was the retired student, making companions in my lone study of the world’s chiefest sages, exploring nature in her secret depths, and riving treasures from her reluctant bosom. At other times I was a rollicking blade, an adept in all mischief, and the very idol of the female sex.

But let me be precise.

It was on the 12th of January-I remember the month and the day, but the Anno Domini has escaped my recollection. The Great Unknown, as he was called, was writing his novels; Byron, too, was just dead, that is all I am certain of. Perhaps both these authors are no longer read, perhaps they will be as enduring as time—I do not know. It was on the 12th of January, however, that I found myself the inheritor of a large fortune. My memory must wonderfully have failed me, since I cannot remember how I came by it, some relation was deceased, I know not whom. I cannot recollect the amount of my income, only that it was very large, and that I was universally considered the happiest of men.

But I was anything but happy. I was the most miserable of the human race. I loved devotedly, and my passion was met unrequited.

The object of my love was very beautiful—oh God! she was angelic. I never saw a face which in the least approached hers in loveliness. Nature -does not Ariosto use the prettiness-broke the mould in which her features were cast.

I loved this woman better than my life.

I had no other life but in constant waking thought, and nightly dream of her. She was all my world. And she hated me in return, and her hatred drove me⸺

No, not mad. I am sane as the coolest and wisest of my brethren. But her dislike affected my health, I neglected my person. My friends wondered and whispered. I overheard their remarks hissing through their closed teeth, and from that moment I shunned them.

Once more, let me be precise. The lady of my love married. Her husband was a frigid, worldly individual, whose blood flowed sluggishly through his veins. He was young, and expected a large fortune, larger even than mine, at his father’s death. His father died, and, marvel of marvels, was found to be insolvent. For his lethargic son, bred to no pursuit, there was not a doit. I sent them money through a channel unknown to her. She might have guessed the source from whence flowed the unfailing stream of gold that supplied daily comforts for herself and husband. She might not. I do not know. Of this only I am certain of, that for four years they subsisted upon the resources with which I furnished them. At length one day she presented herself before me.

I shall never forget it. They say I am mad, but I can recall every incident of this eventful epoch of my life, as vividly as if it were graven with pen of iron on impenetrable tablets. She, the wife of another, presented herself at my feet to implore pardon for the wrong she had done me, for the contumely she had heaped upon me.

I raised her and embraced her. At that moment the door was burst open, and her husband, accompanied by two of his friends, entered the room. It was a plot arranged between them. She was a betrayer. An action was brought, and the damages and legal expenses deprived me of half my fortune. Even my former benefits were turned against me. No one believed my Quixotic generosity. From that period I grew careless, and even desperate. I plunged into wild speculations, and I soon found myself a ruined man. Now, if it please you, I was mad. Almost destitute myself, I married a young creature whose parents were just dead, and who, hitherto, had been bred in the very lap of luxury. I had some talent, but it was not of an available kind. I was not qualified for either trade or profession. I had no expectancy—no means of living, and yet I married a young, delicate girl, penniless herself yes, I was mad, indeed.

From this date misery became my housemate, my bread, it was soon literally bread, was steeped in tears. Yet she, angel as she was, upheld and cheered me-never repining, never giving utterance to a single complaint. Gracious power how it became me to have cherished her! But I did not, I did not, I ill-used her.

Yet she never complained.

Chill penury smote us. I worked as a menial, but could obtain only a scant subsistence. An infant came to add to our care. My poor wife sickened, but she did not die. Grief is strong, but devoted affection and maternal love are stronger still.

I know not whence came the wicked whisper that prompted me to steal, but the suggestion grew to be ever present with me. Some demon must have urged me on. Aye, I will tell you what demon it was. The same that haunts the footsteps of men whose faces are haggard and whose eyes are bloodshot—on whose menial condition society sets the seal of scorn—who work for inadequate wages—who behold wives and children starving on insufficient food. There are frightful demons laying wait in such men’s paths. Heaven send they may soon be exorcised!

I yielded to the wrongful impulse. I can scarcely recollect what I stole. I was hired to convey a package to a coach-office. I remember that it was heavy, and unless my memory has altogether proved treacherous, it was a bale of linen. I have said that I worked as a menial—I, who was once the fashion, had become a ticket-porter. Better that than be dishonest, but I was dishonest notwithstanding.

Better I had died.

But I must go on. I was detected, and committed to prison. The judge was lenient. I had formerly known that judge, and had paid a hundred guineas for a dinner at Long’s, of which he had partaken. He sentenced me only to a month’s imprisonment. When my brief term of confinement was expired, he sent me a bank-note for fifty pounds, and he had succoured my wife and child in the meantime. I fell upon my knees and returned thanks to Heaven.

My affairs now took a better turn. Touched by my misfortunes, some of my wife’s friends set a-foot, among themselves and connexions, a subscription to get us a passage to America. I refused to go; I was incensed at the thought of expatriation; I persisted in clinging to the soil that gave me birth. “The stars are everywhere,” said a friend, endeavouring to unhinge my determination. “Yes,” I replied, “and the sun, and moon, and the green, rejoicing earth also, but I love England and its metropolis—I will abide in London.”

Oh that I had consented to exile, that I had planted my foot in swamp or savannah, that I had scorched myself to fever beneath the fiery sky of the torrid zone! There I should at this moment have been at liberty, and have escaped the consequences of a fearful crime.

When a man has once committed a great fault, there is no redemption for him; no security will be accepted for his subsequent good conduct; no pardon will be extended to him.

From this epoch I was a marked man.

Good conduct would avail me nothing. I had no further right to character. Yet I might have been redeemed.

I might I might—I feel it here in my heart of hearts. I know that my nature was not destitute of good. If they had but have trusted me! They did otherwise, and I went from bad to worse.

I remember that when evil thoughts assailed me at that time, that an influence, begotten of my old studies, sought to win me back. I had been a student—I had “unsphered the spirit of Plato.” My lamp had shone at midnight hour-aye, and till it was eclipsed by the dawning daylight—when I was a youthful and ardent seeker after knowledge. And those nights returned upon me now, and the spirits that I had questioned, came in crowds—in crowds, and with piteous solicitations endeavoured to turn me from the path of guilt. My old college days my old college friends—my old college hopes and aspirations—all came back, and gathered round me, and would not leave me, but pursued me through thronged thoroughfares, and where men stood with money-getting faces, and where the sons of mirth and drunkenness laughed and quaffed from morn to noon, and noon to dew-descending night. For whole weeks they left me never, but attended me whither I went, and still followed me on and on.

They soon quitted me in despair.

For I cast the benign influence behind me, and plunged yet deeper in guilt.

A woman had crossed my path. I knew her immediately: how could I forget her the author of all my misery? Amidst the throng in Cheapside I gazed upon her unnoticed. Her husband had prospered upon the legal damages of which he had defrauded me. He was a great man now, and society caressed him and cherished him. Already an alderman, it was said he would soon be lord mayor. Oh! I knew better than that, for the devil again whispered in my ear.

I laid my plan. I ascertained that the man I hated went at a certain hour to attend a meeting. I rushed home, and took from my poor wife the last wreck of her finery. I pledged it; and with the money procured by that means, purchased an old horse-pistol. I laid wait for the alderman, and fired into his carriage. Ha! ha! my aim was unerring—the ball went through his heart. They seized me on the spot. I was tried, and—oh! Justice, how wert thou cheated! I was saved from the halter on the ground of insanity.

Since that time, I have dwelt here.

Since that time, I have grown old. White hairs cover my temples, and death comes not. Sometimes I feel that I shall never die.

I lie awake on moonlight nights, and wonder where my wife is! where my children! I see them here at times; but I know I am deceived by phantoms. Yet, I feel that they, the issue of my body, and she, my helpmate, are not dead, but breathe and live without these walls.